Essays

My Music Is My Memoir

Although I was writing music for friends and myself from the time I was seven, I never consciously considered becoming a composer. Throughout my training – from the Juilliard Prep through graduate school at Columbia – I was told, explicitly (since that was the attitude of the time,) that a woman could not aspire to be a composer because “you’ll marry and have children.” Although I did marry several times, I never had a child because I believed that the attention I’d lavish on one would cost the concentration that I’d otherwise spend on music. (Until a few decades ago, women instrumentalists, too, were permitted only limited roles; the Vienna Philharmonic, for example, only began to allow women to audition in 1997!)

When I began to compose seriously at Sarah Lawrence College – then still a women’s college where it was believed that women could do anything – I still could not bring myself to call myself a composer, saying instead that “I write music,” when asked what I did.

My family, meanwhile, was focused on my becoming a doctor, a profession for which I had neither aptitude nor enthusiasm (although of course I’m delighted that others do….)

When I was five my family moved from the Bronx (New York City) where I now make my home, to what was then French Morocco. Its striking visual beauty, the extraordinary light, and the non-Western modes, scales, instruments, and vocal techniques embedded in Morocco’s traditional music and religious rites fascinated me. Spending many solitary hours allowed me to read, to practice and experiment with music, and to ponder my daily encounters with inspiring phenomena. Composing became then – and remains – an intimate experience, creating and polishing something elegant and deeply expressive, with the power to evoke emotions, to reach and stimulate the inner life and conscience of the listener.

Once my family returned to New York, I enrolled at the Juilliard Preparatory Division as a violin student, also studying piano, bassoon, and voice. But most fascinating of all was music theory. The theory curriculum was so extensive and so skillfully taught that later throughout my Masters in Theory and Composition and a DMA in composition, I placed out of all theory courses. Such early, deep immersion in music theory generated a formidable technical foundation so natural that, while I am not usually conscious of it while I’m actually composing, its role in my compositional technique is fundamental.

Later, during and after college, while creating music for the Martha Graham, Paul Taylor, and Merce Cunningham dance companies, and composing works for The New York Philharmonic Ensembles, The New York Choral Society, and the Pennsylvania Ballet, I realized that, of course, I was a composer – and one with a distinctive voice and approach, often linking intimate inner landscapes with larger societal issues.

Composing and improvising for dance companies established a visceral connection in my work between music and the body, a connection almost as strong as music has to the emotions and to the soul. While music is intuitively experienced by the body, it is, at its most powerful, a mysterious code best read by the heart. Often it can simultaneously express different – and sometimes divergent – emotional meanings. At its most effective, music bestows a state of grace in which the intensely personal persuasively connects to larger issues, universal concerns or communal experience.

Much of my music has been a synthesis of the personal and political because I believe that the artist’s can be a prophetic voice which can touch others’ conscience and consciousness. Especially in our own time, the need for such voices is urgent. Reinforced by my role as a Fulbright Senior Specialist on the Council for the International Exchange of Scholars, my work became increasingly responsive to global issues:

A cantata for orchestra, chorus, and four solo voices, Toward a Time of Renewal was commissioned by the New York Choral Society for their 35th Anniversary Concert in Carnegie Hall. It took on distressing concerns almost 30 years before they were recognized as vital to the society at large. Written in collaboration with poet Denise Levertov, Toward a Time of Renewal juxtaposes the collective and the personal: the connections between the brutality of war and that of domestic violence, between the universal and individual need for pure water, the beauty and promise of the natural world and our personal and collective responsibility to maintain it.

Lagrimas y Locuras, Mapping the Mind of a Madwoman,  commissioned by Ana Cervantes’ Monarca Project, deals with the silent plight of third world women in Mexico, Brazil, Argentina, and New York City. Parallel issues in a different region and culture, motivated Who is that Stranger, a song cycle based on the oral poetry of illiterate, anonymous women of Yemen and the West Bank.

commissioned by Ana Cervantes’ Monarca Project, deals with the silent plight of third world women in Mexico, Brazil, Argentina, and New York City. Parallel issues in a different region and culture, motivated Who is that Stranger, a song cycle based on the oral poetry of illiterate, anonymous women of Yemen and the West Bank.

Much of my recent composition has involved collaborations with non-musical entities to create music that speaks to and assists in missions whose objectives I shared. In addition to working with creative and musical colleagues, I have collaborated with NYPD Firehouses, animal welfare organizations, and charitable institutions – reaching, through our shared values, beyond a specifically musical world to a wider, shared universe:

The Firefighters’ Prayer is the result of my work with the NYPD Firefighters after 9/11, as part of their process of grief and healing.

As Consolidated Edison’s Composer in the Metropolis (NYC), I worked with an all-amateur, unauditioned, demographically diverse chorus on a work focused on the wisdom of the natural world and the meaning and value of patience and serenity in its presence.

Commissioned by ArtsVenture for the Fairbanks [Alaska] Humane Society, Take Home a Dog was part of the Humane Society’s outreach to the community on behalf of stray or abandoned animals. It is scored to include actual barking refrains, which have posed liability issues for presenters several times and required the invention of canine notation.

Often, by quoting and elaborating on the musical and historical legacies of various locales and cultures, my music helps to celebrate and preserve them.

Scalerica d’Oro a suite for cello and dumbek, was commissioned by the Spanish and Portuguese Synagogue in the City of New York. It incorporates melodies and tropes of the Congregation’s unique historical heritage – and invites participation by those listening.

Runes and Ritual for Piano Quartet, nominated for the 2012 Pulitzer Prize in Music, was commissioned by the James Piano Quartet and Sweet Briar College as an exploration of the history, rituals, and indigenous music of the Blue Ridge region of Virginia

Summer Synchrony, commissioned by Meredith College, is a four-movement piano duet, each movement requiring a different level of pianistic skill so that each young member of Octavia, Meredith’s piano studio, could participate in its performance. Thus Summer Synchrony can be performed as a four movement, four-hand sonata by one duo or by multiple, sequential duos at different levels of expertise. The imagery of Summer Synchrony recalls my childhood summers with my grandparents in the Hudson Valley, the sounds of birdsong, of folksongs, of church bells – a warm amalgam: a collage of countryside companionship, a tribute to my personal joy in playing piano duets with friends, and an invitation to young pianists to play with their own friends.

An important aspect of my mission a composer has been making meaningful contact with diverse audiences. For some decades I have relished giving introductory lectures for the New York Philharmonic, the Dallas, Billings and New Jersey Symphonies. In speaking to audiences, I act as a hostess, welcoming listeners into the music which has been my spiritual home, inviting the audience to relate to the creative process that produced that music and which they might then find inside themselves as well.

Most of my solo songs, for example, grow directly out of my personal life. They are an ongoing intimate journal, from love songs to elegies, from the spiritual to the absurd They reflect all aspects of my daily life: relationships, responsibilities, pain or consolation. Even my love songs tend to reach through the intimately personal to more universal experience, as meditations on commitment and purpose, mortality and eternity.

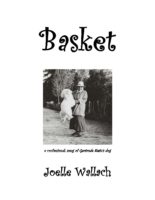

Among my muses are the cats and dogs who have been a meaningful part of my life, inspiring and consoling me.  I celebrate them as loving clowns and earnest companions. Their charm, dignity, sensitivity and humor is captured in songs like PAX which pays tribute to my cat Suri as eloquent spiritual teacher. Much sillier are songs like Alley Cat Love Song, Kneel Before Me, or Basket, a recent hilarious concert aria, written in the voice of Gertrude Stein’s poodle.

I celebrate them as loving clowns and earnest companions. Their charm, dignity, sensitivity and humor is captured in songs like PAX which pays tribute to my cat Suri as eloquent spiritual teacher. Much sillier are songs like Alley Cat Love Song, Kneel Before Me, or Basket, a recent hilarious concert aria, written in the voice of Gertrude Stein’s poodle.

It’s worth noting that despite Stein’s wealth and her international role in the arts, she would not have been allowed to vote until 1920 in the United States nor in France until 1944. Since her time, the role of women in the Western world has expanded considerably – including the possibilities for women in music. In the United States, the 19th Amendment, passed in 1920, not only gave women the right to vote, but also to own property, to serve on juries and to enjoy the privileges and obligations of full citizenship.

In celebration of the 100th anniversary of that 19th Amendment, Suffrage Signatures was commissioned by the Canta Libre Chamber Ensemble, supported by a grant from HumanitiesNY with funds from the National Endowment for the Humanities. The names and public faces of the century-long movement for women’s suffrage are familiar to us, but not those women’s private lives, moods or relationships. Inspired by the Suffragists’ personal letters, Suffrage Signatures is a series of musical interpretations of the informal, private voices captured in their letters, which are available for perusal in the archives of the New York Public Library.

I am touched, honored and grateful that, along with theirs, my own personal papers, photographs and music are now also archived in the Research Collection of the New York Public Library. Many can also be seen on this website.

Releasing the Caged Bird

Completing a Work

Last week I completed a piece. Just days ago, I was absorbed in its compositional momentum and its specific sounds, sonorities so sweet and compelling I’d hear them in bed each morning waking me up. That piece – the Caged Bird piece – is to be sung by 75 children along with French horn and piano. Through my weeks of work on it, voices of imaginary children sang inside me, keeping me company, keeping me busy, keeping me believing there was something in the world urgently worth doing. Each day of those past two months, the imaginary sound of singing children steered me to the piano before shower or breakfast.

Last week I completed a piece. Just days ago, I was absorbed in its compositional momentum and its specific sounds, sonorities so sweet and compelling I’d hear them in bed each morning waking me up. That piece – the Caged Bird piece – is to be sung by 75 children along with French horn and piano. Through my weeks of work on it, voices of imaginary children sang inside me, keeping me company, keeping me busy, keeping me believing there was something in the world urgently worth doing. Each day of those past two months, the imaginary sound of singing children steered me to the piano before shower or breakfast.

Five nights ago, I realized the piece was complete. I ran down to the corner mailbox in the middle of the night to send it off to the printer downtown Continue reading

While Hope Remains: Envisioning the music

A Composer’s Response to 9/11

Winter didn’t need to come this year; New York was already bleak under October’s continuing cloudless sky. Not waiting for snow, we were waiting for smallpox, for nuclear clutter, for plagues we’d only read about in history and in cattle.

Winter didn’t need to come this year; New York was already bleak under October’s continuing cloudless sky. Not waiting for snow, we were waiting for smallpox, for nuclear clutter, for plagues we’d only read about in history and in cattle.

Our shared world suffused with recurrent panic, dread and disillusionment; my interior world had been strangely silent for a month. No music inside me, and any music outside found no resonance within.

Ice sculpture commemorating firefighters of 9/11

Eldridge Street Synagogue

A Site-specific Notion

Auditory landscapes are most evocative for me, evocative of people’s lives and practices, and of moods. So silence in the sanctuary of one of the oldest, most historic houses of worship in New York, the Eldridge Street Synagogue on the Lower East Side, troubles me. The site has been restored to habitability and it now serves as a museum of urban immigration.

Auditory landscapes are most evocative for me, evocative of people’s lives and practices, and of moods. So silence in the sanctuary of one of the oldest, most historic houses of worship in New York, the Eldridge Street Synagogue on the Lower East Side, troubles me. The site has been restored to habitability and it now serves as a museum of urban immigration.

It is usually silent now except for footsteps and hushed conversation. But for generations the sanctuary rang with a kaleidoscope of haunting melodies, changing with the arrival of each generation of Jews finding their first American refuge on the Lower East Side. Continue reading